How do we monitor the Hikurangi Subduction Zone?

We recently took a deep dive into what, and where the Hikurangi Subduction Zone is. Today we are going to look at how we monitor and build up our understanding of our largest plate-boundary fault, and better understand its potential impact.

The Hikurangi Subduction Zone is the largest source of earthquake and tsunami hazard in New Zealand. It attracts a huge amount of international scientific attention because many characteristics of the Hikurangi Subduction Zone can give us insight into why large earthquakes happen on these types of plate boundaries, and why tsunamis are generated from subduction zones.

If you missed our first Hikurangi story, you can click here to catch up on the background.

24/7 Monitoring

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, we have our 24/7 monitoring centre keeping eyes on more than 800 instruments for all perils across Aotearoa New Zealand and the Southwest Pacific. Our large seismic network allows us to quickly locate earthquakes in and around New Zealand, and even those from far overseas.

We also have a network of GNSS instruments (commonly referred to as GPS) the position of which, relative to the earth’s surface, can be determined very precisely. We compute a daily position for each of our stations so we can track the deformation caused by the interaction of the Australian and Pacific tectonic plates. Its these sensitive instruments that allow us to detect slow slip events along the Hikurangi Subduction Zone and understand how our land changed and deformed due to an earthquake.

Keeping an eye on tsunami

Not only would a large Hikurangi Subduction Zone earthquake cause severe to extreme shaking across the North Island and the top of the South Island, but it would also generate a large tsunami.

Because of this (and other tsunami from around the world that could arrive in Aotearoa), we have a network of 18 coastal sea level gauges near New Zealand’s shores, picking up possible tsunami activity. The gauges are across the North and South islands, at Raoul Island and Wharekauri Chatham Island, and one in Lake Taupō.

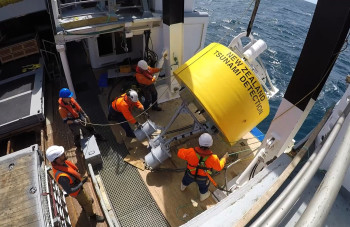

For tsunami monitoring in deep water, we have the DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami) sensors. Introduced in 2019, these twelve deep-ocean instruments are located at selected points close to the Hikurangi, Kermadec, Tonga, and Vanuatu (formerly New Hebrides) trenches where they can detect and measure tsunami that could reach our shores, and those of our pacific neighbours, in less than a few hours.

Though lots of research is in progress, DART sensors are currently the only available accurate way to rapidly detect and confirm a tsunami has been generated before it reaches the coast, or to make sure that no tsunami has been generated following a large earthquake or other possible trigger events such as under-sea landslides and volcanic eruptions.

The DART network is designed to monitor tsunami in and from the Hikurangi, Kermadec, and Southwest Pacific, providing data periodically that helps us model the tsunami and estimate how it might affect our coastlines.

If there is a tsunami threat, official warning information will come from the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), however, for a local-source tsunami which can arrive in minutes, there is not enough time for an official warning, it is important to recognise the natural warning signs and act quickly.

A large Hikurangi Subduction Zone earthquake will generate a tsunami which could reach our shores quickly – this is where it is important to remember the ‘Long OR Strong get gone’ safety messaging. An earthquake that lasts more than a minute OR makes it hard to stand up is a natural tsunami warning. As soon as the shaking stops, move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can to get out of the tsunami evacuation zones.

Learning more about the Hikurangi Subduction Zone

GeoNet has a key role to play in helping build our understanding of the Hikurangi Subduction Zone - from data collection, analysis, and sharing to 24/7 monitoring and co-development of rapid scientific analysis tools, but we can’t do it alone! There are a number of scientific research projects going on at GNS Science that specifically focus on trying to better understand this important plate boundary fault and GeoNet engages with these projects in a variety of ways.

We engage directly though collaborations and consultation to support the development of tools and enabling enhancements to network configurations and data processing. More indirectly we engage through providing data and receiving feedback on data processing and analysis. Many programmes are also crucial to building up our collective understanding of Hikurangi behaviour and processes that inform the scientific modelling that underpins hazard and risk assessment, including rapid response tools!

We look at some below:

RCET — Rapid Characterisation of Earthquakes and Tsunami

The RCET programme is developing a suite of real-time tools that can be used to rapidly extract more information about large earthquakes and tsunami that occur in New Zealand and the Southwest Pacific. They can help quickly build a picture of how large an earthquake really is, where the rupture has occurred, and what the forecast tsunami at the coast might be. Some of these tools are already being used by GNS science responders in the 24/7 monitoring centre and by the Tsunami Expert Panel. GeoNet partners closely with the RCET programme to help develop, implement, and share rapid scientific information.

RCET is a MBIE (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment) Endeavour funded programme (2020-2025).

PULSE — Physical processes UnderLying Slow Earthquakes

The GNS-led PULSE project, with major collaboration and contributions from international partners, has given scientists a better understanding of the way plate tectonic stresses builds up and are dissipated on the Hikurangi subduction zone.

A diverse array of over 80 instruments has been installed onshore and offshore, to capture crustal deformation and seismicity related to slow slip events, including seafloor pressure sensors, temporary GPS instruments and seismometers onshore and on the seabed.

PULSE is a Royal Society/Te Apārangi Marsden funded project (2021-2024)

Read more on the PULSE project here.

It’s Our Fault

Through the It’s Our Fault Project scientists have discovered evidence of four past subduction zone earthquakes that have impacted the Wellington and Marlborough region in the past 200 years. Evidence for these earthquakes comes from sediment records from coastal lagoons that show sudden land level changes and tsunami sediments that are characteristic “geologic signatures” of subduction zone earthquakes.

Read more on the Its Our Fault project here.

Turbidites

Another current project is using offshore sediment cores from the Hikurangi Subduction Zone to study turbidites. A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a submarine sediment flow. These underwater sediment flows can be triggered by the shaking of large earthquakes, much like landslides on land. Studying turbidites can tell us about the timing and location of past large earthquakes on the subduction zone.

In a project with Victoria University of Wellington and NIWA, GNS Science are studying the record of turbidites offshore of Hawke Bay to better understand how often and how large subduction earthquakes are underneath the Napier area. In the image of sediment cores below, each deep brown layer is a soil layer that is overlain by estuarine mud, each soil-mud contact represents land level change from a subduction zone earthquake.

More Projects looking at the Hikurangi Subduction Zone

Ngā Ngaru Wakapuke — Building resilience to future earthquake sequences

Solving the enigma of tsunami earthquakes

Next up is the final in our Hikurangi Subduction Zone series. Now we know all about the Hikurangi Subduction zone we look at how you can be prepared for the hazards that it can produce.

Earthquakes can occur anywhere in New Zealand at any time. In the event of a large earthquake: Drop, Cover and Hold.

Remember Long or Strong, Get Gone : If you are near the coast, or a lake, and feel a strong earthquake that makes it hard to stand up OR a weak rolling earthquake that lasts a minute or more move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can, out of tsunami evacuation zones.

Know what to do?

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) has a great website with information on what to do before, during and after an earthquake.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for natural hazards. Toka Tū Ake EQC’s website has key steps to get you started.

Media Contact: 021 574 541 or media@gns.cri.nz