The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami shocked the world – are we better prepared 20 years on?

On December 26, 2004, an M9.2 earthquake in the Indian Ocean caused a devastating tsunami that tragically claimed the lives of around 230,000 people and affected 14 countries. This event marked the first major global disaster of the 21st century and remains one of the deadliest in recent history.

November 5 is World Tsunami Awareness Day, and this year the aim is to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Indian Ocean Tsunami by passing on its lessons to a new generation of children and young people. Anyone in their early 20s or younger probably doesn’t remember the 2004 tsunami, but for those of us who do, the scale and devastation is vividly etched into our memories.

The Indian Ocean Tsunami led to a better understanding of the risk and the huge tragedy that can result from a large subduction zone plate boundary earthquake, including ground shaking for more than 10 minutes and large tsunami. In this case causing the tragic loss of hundreds of thousands of lives around the Indian Ocean, especially nearby in Indonesia.

Although this earthquake was off the coast of Indonesia, it can happen in the same way in Aotearoa New Zealand, via our Hikurangi Subduction Zone. This highlighted the need to be better prepared.

So, what have we learnt since this disaster?

We spoke to Graham Leonard, GNS Principal Scientist, who has been studying the impacts of tsunami for 25 years.

We travelled to Thailand in 2006 to study the way warnings played out for people farther away. This highlighted the importance of evacuating immediately on natural warning signs – long ground shaking and unusual ocean behaviour. Also, that informal warnings from one person to another were important.

Then in 2008 we helped local authorities in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, evaluate their first tsunami exercise since the 2004 tragedy. We learnt firsthand how devastating the event had been at this ground zero location, how important immediate evacuation is, that it’s important to walk rather than drive, and the value of vertical evacuation in buildings. Many large evacuation buildings have since been built, with help from donors, because high ground is far away in Banda Aceh.

These overseas learnings led to the development of Aotearoa New Zealand evacuation zone maps, consistent red-orange-yellow zones nationwide, so people could tell where they were at risk and how far they needed to move to be safe.

As the calculation of these zones rolled out nationwide, communities were encouraged to plot their evacuation routes on the maps. In 2010 this led to the local community in Island Bay, Wellington asking “why don’t we just paint a blue line around the zone so everyone can see it?”.

The first lines were painted in early 2011, and although there was some controversy in terms of how far and high the zones were, within weeks of painting the lines another tsunami tragedy shocked the nation, this time off the coast of Japan on 11 March 2011, again with horrific consequences – about 20,000 fatalities mostly from the tsunami. This disaster led to people questioning if the zones were high enough and helped them become a permanent fixture in many coastal towns around Aotearoa New Zealand.

Graham visited Japan in 2011 and interviewed emergency managers from some of the hardest hit communities, the main messages to us was to evacuate immediately, and don’t drive. We also learnt from Japanese studies that towns with regular drills correlated to a higher survival rate.

Back home we simplified the messaging, moving to emphasising the ‘Long OR Strong, Get Gone!’ message based on that experience, and the simple and visible blue lines in places that were painting them.

What about warnings?

Most of Aotearoa New Zealand’s warning and evacuation framework was built in response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami, and it has changed considerably since. We now use tsunami forecast models to establish the potential threat in pre-defined coastal zones. The threat levels can be used to inform evacuation decisions based on already-planned evacuation zones and routes.

Although Aotearoa New Zealand is now well served for distant and regional tsunami, we still rely on natural warnings (feeling high levels of, or long-lasting shaking, and unusual sea behaviour) for local-source tsunami – earthquakes or triggered undersea landslides near our coast.

How do we know a tsunami is coming?

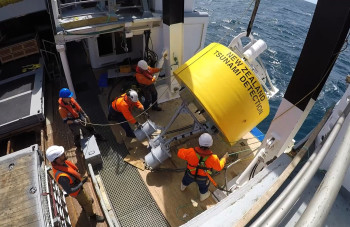

The New Zealand seismograph network includes seismic sensors which can detect potential tsunami-generating earthquakes occurring off the New Zealand coast. Analysis of the seismic waves can determine whether the event is likely to have disturbed the sea floor and caused a tsunami, we then have 12 Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami sensors (DART) monitoring changes in sea level deep in the Pacific Ocean that help us detect and understand tsunami. Finally we have a network of 18 coastal sea level gauges near Aotearoa New Zealand’s shores, to pick up possible tsunami activity as it reaches our shores. Read all about the DART network and how it works here.

For tsunami coming to Aotearoa New Zealand from around the Pacific, we have more time to evaluate and assess the possible threat – sometimes up to 12 hours if the tsunami is coming from South America, Alaska, or Japan.

If the tsunami is generated by a large earthquake, our National Geohazards Monitoring Centre (NGMC) will pick up the earthquake signals and be able to activate our duty officers and the Tsunami Experts Panel (TEP) right away to help build understanding of the potential threat to Aotearoa New Zealand. Otherwise, if we receive a warning from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center in Hawaii, or one of our DARTs activates, the NGMC immediately contacts our duty officer who will escalate to the TEP to assess the information.

Through these teams, GNS provides advice to NEMA who issue national warnings and support regional Civil Defence and Emergency Management Groups with regards to regional warnings as well. DARTs from Aotearoa New Zealand and other countries, as well as national and international coastal sea level gauges, help the tsunami experts in the TEP refine our estimates of the tsunami arrival and the potential effects on Aotearoa New Zealand coastlines. Our sensor information also feeds into the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center’s estimates of the tsunami threat.

For a local source tsunami, which could arrive within minutes, there won’t be time for an official warning. Drop, Cover, and Hold, and Long or Strong, Get Gone are crucial messages to remember when you feel shaking. Our analysts at the NGMC follow the same processes, and then immediately get to work – analysing the event and escalating to duty officers and the TEP to ensure the best possible advice is available as fast as possible to NEMA.

However, it is important to recognise the natural warning signs and not wait for an official warning. As soon as the shaking stops, move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can to get out of the tsunami evacuation zones. Even if you cannot get out of your evacuation zone, go as far or as high as you can – every metre makes a difference. Remember, Long or Strong, Get Gone.

Read: About tsunamis, learn the warning signs and the right action to take

Find: Your tsunami evacuation zone

Only messages issued by the National Emergency Management Agency represent an official warning status for New Zealand. Go here for the latest NEMA updates.

Media Contact: 021 574541 or media@gns.cri.nz