Data Archaeology – Examples from a High Profile Dataset

Welcome, haere mai to another GeoNet Data Blog. Today’s blog is about data archaeology, dealing with old data and how we sometimes have to work around not having all the information we ideally want. If you are a fan of Indiana Jones, this one is for you.

GeoNet is very careful about recording and making available all the information about the data we collect. We call this metadata, information about data that helps you use our data effectively. We touched on this in earlier blogs about new seismic, GNSS, and tsunami gauge monitoring sites installed in late-2022, and more recently about metadata curation in our seismic data archive.

When we install a new site to collect data, getting the metadata right is relatively easy as we have the equipment available and importantly, we have well-established procedures, and everyone knows what information needs to be recorded and how we use it.

While GeoNet started in 2001, we manage some datasets that start earlier than that, datasets collected by GNS Science and its predecessor organisations like New Zealand Geological Survey. In some cases, especially if those datasets weren’t stored in a formal, organised database, some of the metadata we collect nowadays isn’t available. Either it wasn’t collected or has been lost over time.

If we want to take some of these old data and make them available through one of GeoNet’s modern data delivery applications, we might have problems. Those applications rely on our Delta metadata database, and if we don’t have the necessary data in Delta, we can’t use the modern applications. To solve this, we have to do some data archaeology, or more specifically, metadata archaeology. This is where we call on Indiana Jones!

Te Wai ā-moe (Ruapehu Crater Lake) temperature (and water level) data

The temperature of Te Wai ā-moe (Ruapehu Crater Lake) is one of the more high-profile datasets we collect. We also collect water level data, but we are going to talk most about temperature today. Read any Ruapehu Volcanic Activity Bulletin and it will always discuss lake data, especially temperature. A lot of this dataset pre-dates GeoNet and we don’t have all the metadata we collect nowadays.

We recently moved some of these data from our soon to be deprecated (geeky word for turned off) FITS database to Tilde, our newer low-rate data delivery application. FITS didn’t use Delta for its metadata and when we started to migrate the data to Tilde, we realised we didn’t have all the information we needed.

Data collected by automatic datalogger

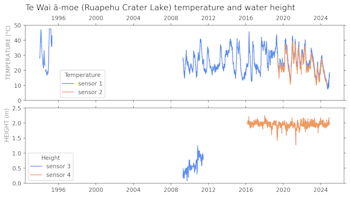

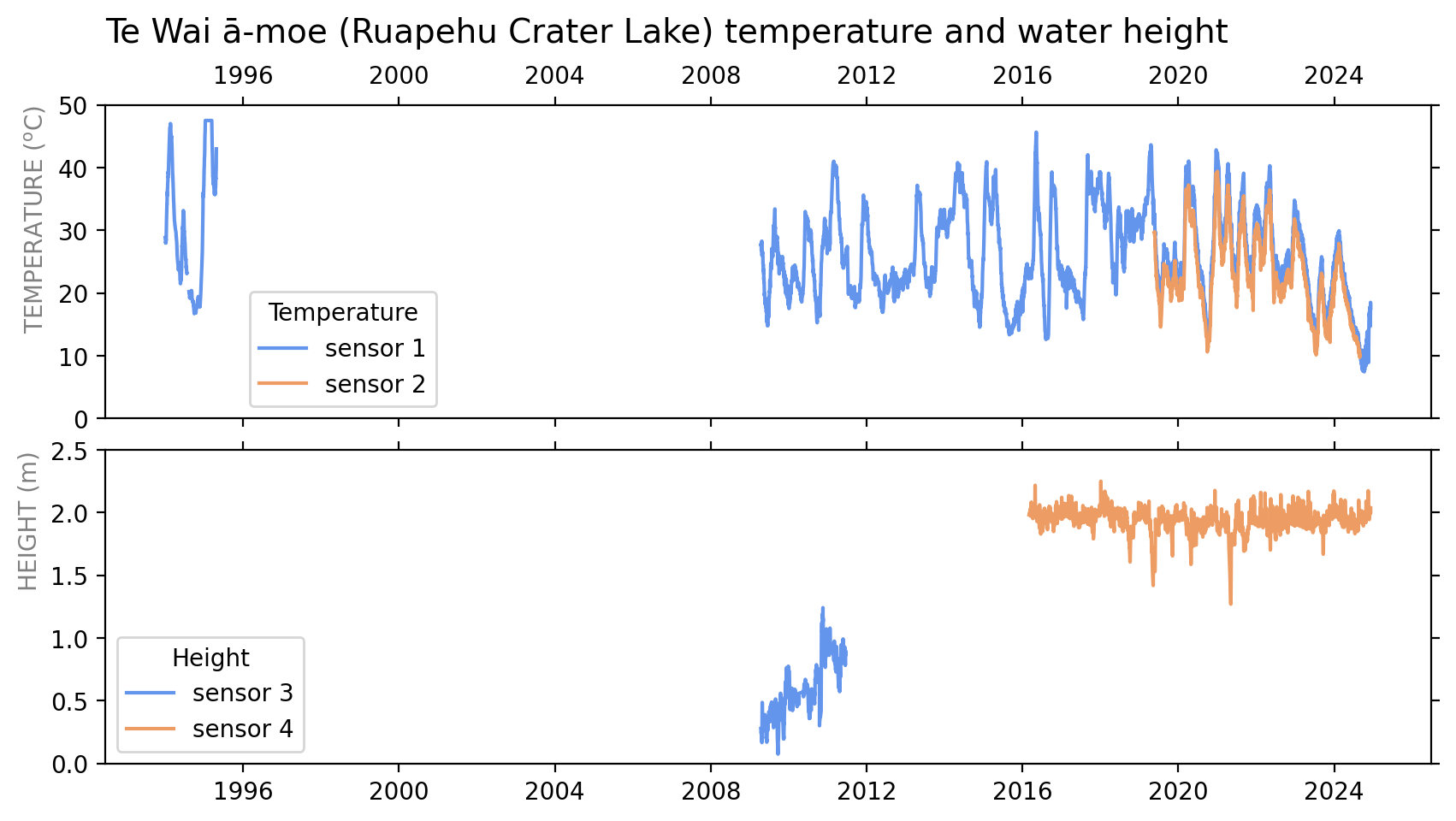

We’ve collected temperature (and water level) data automatically with a data logger at Te Wai ā-moe for many years. We have a little temperature data from 1994-95 and then pretty much continuous data since 2009. Over time, we’ve had two sensors that collect temperature data and two for water level (or height, as we measure how much water is above our sensor).

While we have a pretty good record of the work done to maintain the site that collects the data, when we needed information for Delta, we were missing some important facts about the sensors that were used – the make and model, and the serial numbers. This is information we now regularly record and provide through Delta.

The make and model are important as they help a data user understand any limitations the sensor might impose on the data that were collected, which in turn will prevent the data user from drawing the wrong conclusions about some characteristics or patterns they might find in the data.

How do we solve the problem of not knowing sensor make, model, and serial number? Simply, we can’t! What we’ve done is list these as “unknown”, specifically “Unknown-sensor-make”, Unknown-sensor-model”, and “Unknown” (for the serial number) in our Delta database. We need these fields present in Delta for self-consistency checks, and while “unknown” isn’t ideal, it allows those records to pass the checks and for us to be able to use the data in Tilde. If a user goes into Delta to check the sensor make or model, something we encourage you to do, and finds “unknown” it’s a flag to be a little more cautious about the data and how you interpret it.

Below is part of the file in Delta which lists which sensor is installed at each site. This entry shows a temperature sensor at Te Wai ā-moe (Ruapehu Crater Lake) – station RU001, for which we are missing some information about the sensors.

Make,Model,Serial,Station,Location,Azimuth,etc etc

Unknown-sensor-make,Platinum Resistance Thermometer,Unknown,RU001,01,0,etc etc

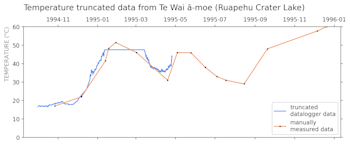

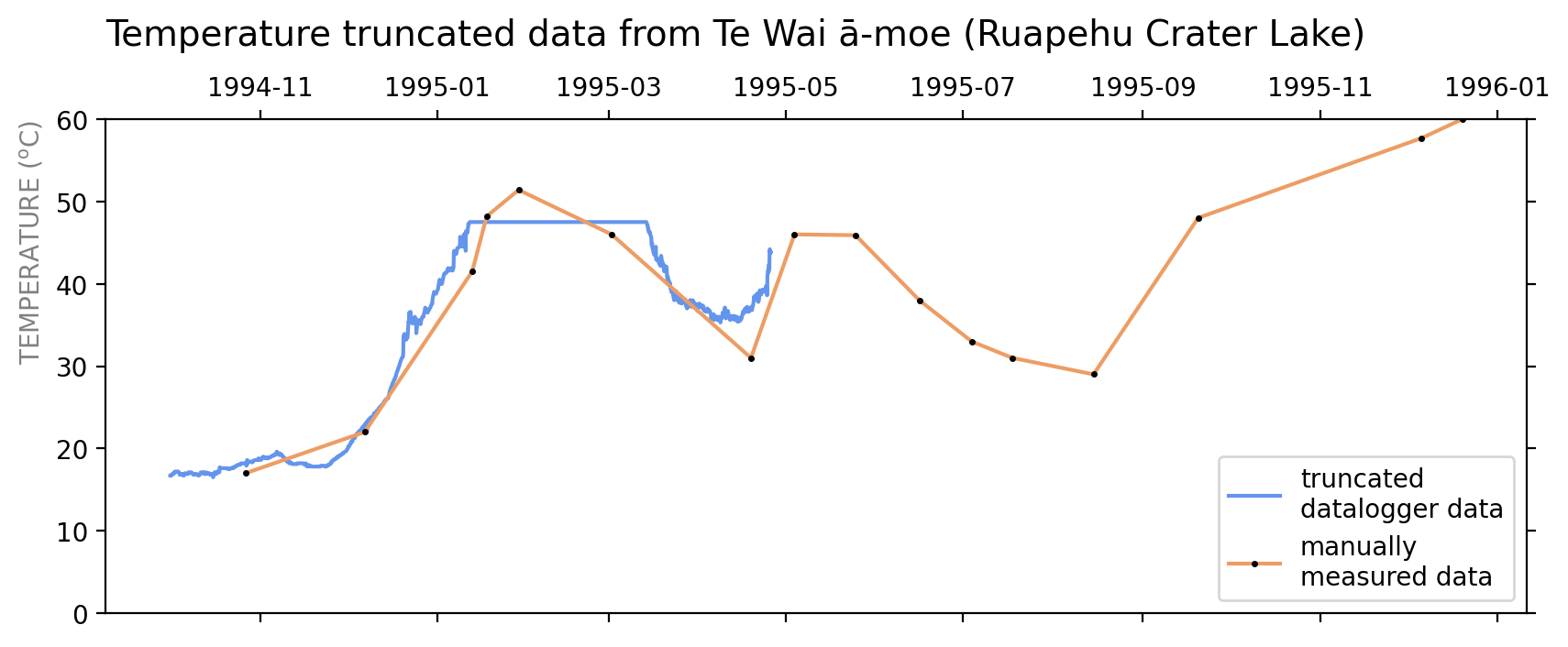

A good example of why we need to understand sensors occurred in early-1995 when the temperature of Te Wai ā-moe was unusually hot. This was a few months before the 1995-96 eruptions, and probably related, but that is a story for another day. Between the sensor and the datalogger, they could not record a temperature higher than 47.5⁰C. When the lake exceeded that temperature, which it did for two months, all temperature data showed 47.5⁰C. This is a real oddity in the data and something we ideally want our data users to be aware of. But without the sensor and datalogger information we can’t provide any reference material for that. A user would have to know to look in the relevant Volcanic Activity Bulletin from 1995, and while it’s available, why would anyone think of looking for it?

Data collected manually

Except for a short period in 1994-95, prior to 2009 all Te Wai ā-moe temperature data were collected manually when someone visited the site and stuck a measuring device into the lake water. Originally, that measurement device was a thermometer and at some time volcanologists started using a thermocouple. Our problem is that we don’t really know when volcanologists stopped using a thermometer and started using a thermocouple. And in reality, there probably wasn’t one instant in time when that happened. There were at least two groups collecting these data and their transition from thermometer to thermocouple won’t have been at the same time.

This all matters because thermometers and thermocouples behave differently and have different measurement errors. For a thermocouple the error of measurement is about 2.2⁰C for the temperature range we are measuring at Te Wai ā-moe, and for a thermometer it probably depends on make and model, but elsewhere we have used a measurement error of 0.5⁰C.

In about 2015, when we were preparing the data to load into our old FITS database, we found two files containing temperature data. Both were collated from observations made earlier and were probably not the “original data”. The original data would have been in the field books of the volcanologists who made the measurements and were not immediately available, as they were at least 20 years old. At the time, we made the assumption that the file with older data contained measurements made by thermometer, and the file with newer data measurements made by thermocouple. This proved to be incorrect.

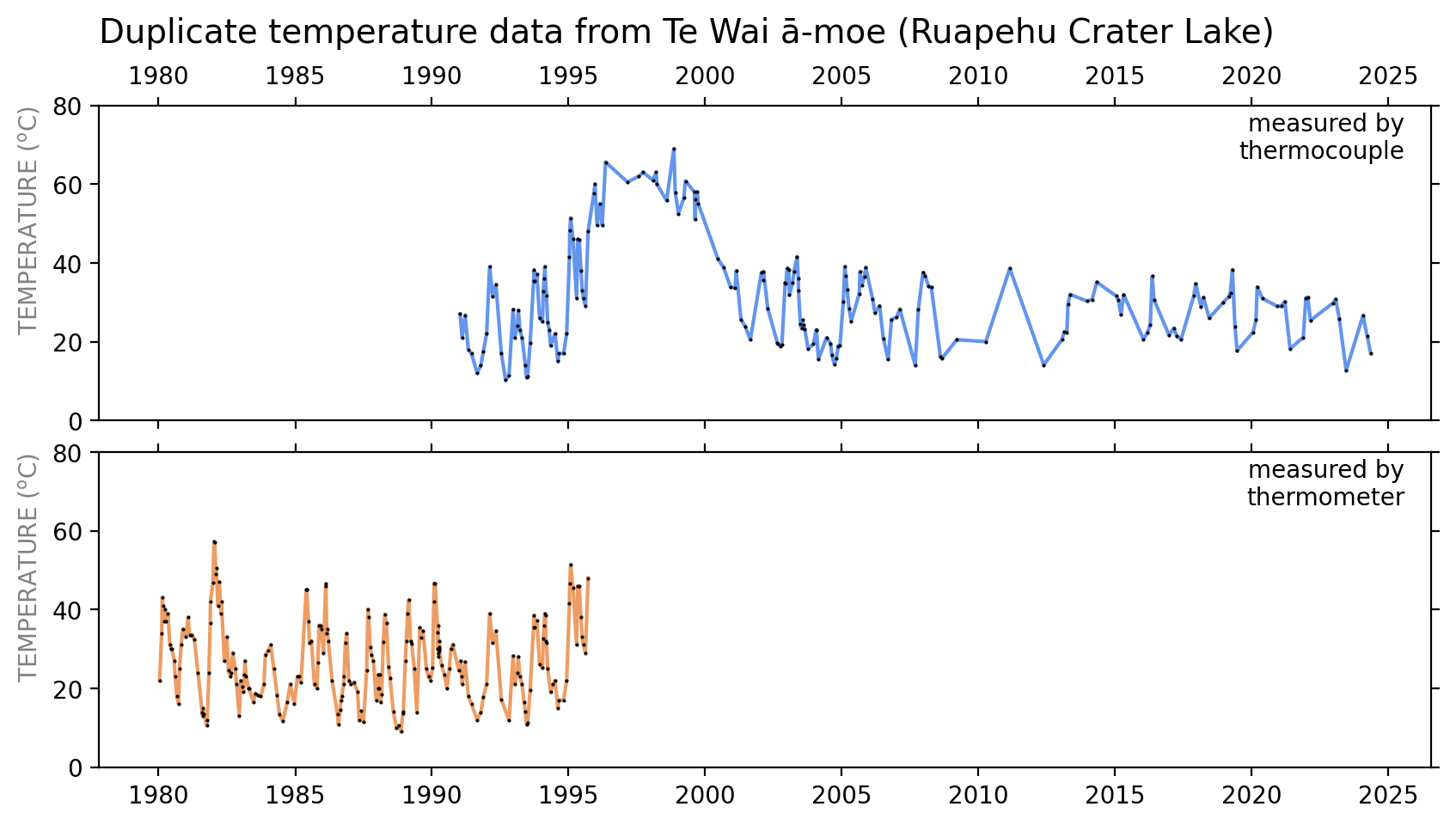

In 2024, after we transferred the temperature data to Tilde, we realised that the two data files we’d initially loaded into FITS contained some data in common. Our assumption that one file contained thermometer data, and one thermocouple data meant we had the same data in Tilde twice, listed once as being collected by a thermometer, and once by a thermocouple. If this sounds a little complicated, this graph should make it clear.

If you just want to graph the temperature over time, the duplicate data doesn’t cause you any real problems, and you’d probably not even notice – no one did in the last 10 years or so! But if you wanted to calculate some statistics from the temperature data, it would be a problem as would be counting some data twice. And it’s not tidy, and if we do nothing it will cause confusion sometime in the future, maybe when no one remembers what happened. But how do we resolve the problem?

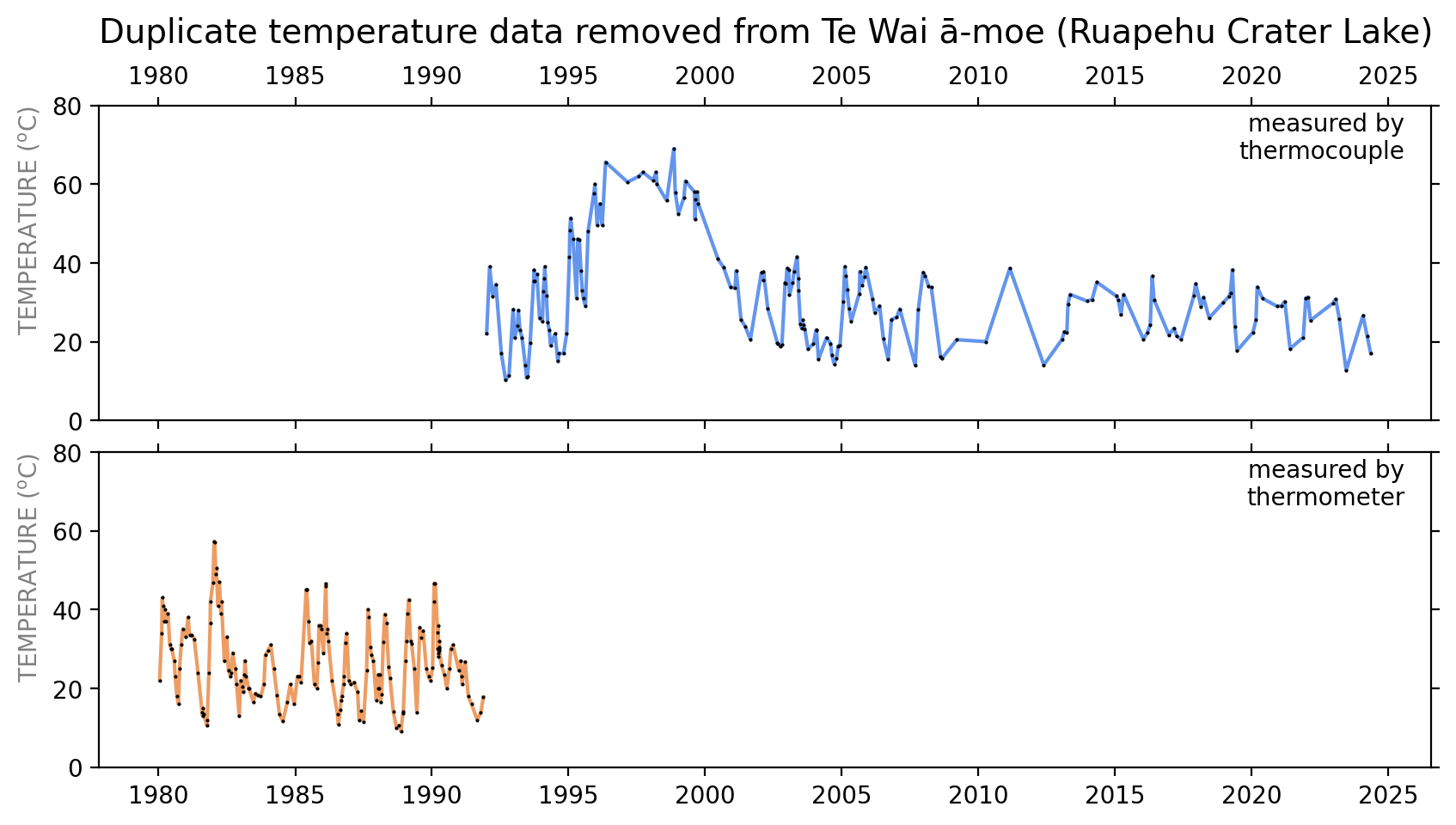

Fortunately, there are three staff who collected some of those data from that period still working at GNS Science, and we asked them for help. Two said they had only ever used a thermocouple, one from 1988 onward, and another from the mid-late 1990s onward. A third said they first got a thermocouple in the early 1990s, and before that used a thermometer. In the end, we made the informed, but still arbitrary, decision that data before 1 January 1992 would be described as collected by thermometer, and data after that date by thermocouple.

We made the changes to the data in Tilde and if you access it now, you’ll find no duplicates and a clear distinction between thermometer and thermocouple measurement methods.

Are there other situations like this, and does it really matter that much?

No doubt there are other cases of historic data with incomplete or inconsistent metadata. We have a similar situation with data collected by datalogger from the volcanic lake at Inferno Crater, Waimangu. We don’t have complete metadata there prior to starting to experiment with our envirosensor datalogger system in 2017.

Our mainstream seismic and geodetic (GNSS) metadata are in excellent shape, at least for the digital data era, from 1986 for seismic and from 2002 for GNSS. Our older seismic data are "paper charts" of ground shaking that date back about 100 years and are less dependent on metadata than more modern recordings.

So, does all this stuff really matter? Should we be spending our time on more important things and worrying less about old data and incomplete metadata? The answer to those questions depends on whether or not you want to use some of the old data. If you do, then our efforts to get the metadata as right as we can, will impact how well you can use the data.

That’s it for now

This isn’t the first blog to talk about GeoNet metadata and it probably won’t be the last. It’s an important, but often undervalued, part of any dataset. Good data management is one of our core roles in GeoNet, and metadata is part of that management. If you want to use a dataset without all its metadata, then you’ll probably have some difficulties.

Data archaeology can be slow, fiddly, and at times a frustrating thing to have to do. But when the see the finished product, even when you know it’s still imperfect, it’s worth the time and effort. Even if no one else notices!

You can find our earlier blog posts through the News section on our web page just select the Data Blog filter before hitting the Search button. We welcome your feedback on our data blogs and if there are any GeoNet data topics you’d like us to talk about please let us know!

Ngā mihi nui.

Contact: info@geonet.org.nz