Our deep-ocean eyes and ears - Diving into the science keeping Aotearoa and the Pacific tsunami-safe

Our place in the Pacific puts us at risk from many different tsunami sources, but even some of the biggest earthquakes originating in the Kermadec Trench are not able to be strongly felt in New Zealand. Offshore seismic events may generate a tsunami that can travel 800km/hr in deep waters to reach our coasts within an hour, without any obvious natural warning. We call these “stealth tsunamis”, and New Zealand’s special geological situation makes us particularly at risk from them.

Helping to turn the tide on tsunami science, 12 DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami) systems are monitoring changes in sea level deep in the Pacific Ocean.

Science never sleeps. Every minute of every day GNS Science is monitoring our natural hazards, with expert eyes on information received from instruments in, on, and around our borders.

A vast range of scientific monitoring programmes are in place to keep the country safe, with more than 9,100 sensors, gauges, cameras and other equipment strategically placed throughout Aotearoa and the Pacific to pick up even the smallest seismic and volcanic activity, the signs that danger may be heading our way. Knowing when hazard events might happen and how they are likely to behave is critical to guiding the nation’s response, and, with over 15,000 kms of coastline, one of the most significant hazards we must monitor and prepare for is tsunamis.

Coastal sea level gauges are placed near New Zealand’s shores, picking up possible tsunami activity. The network consists of 18 stations across the North and South Islands, at Raoul Island and Wharekauri Chatham Island, and one in Lake Taupō. Until recently, the shallow water instruments provided the extent of our tsunami monitoring capability, telling us when tsunami waves have arrived on our shores.

Over time and across the globe, advancing technology has allowed for faster, better, more reliable tsunami detection. With nearly $50M of government funding, New Zealand’s investment in the DART network has engineered a transformational change in the speed and accuracy of tsunami warnings and de-escalations – keeping us and our Pacifica neighbours safer by improving people’s ability to respond.

The DART network was introduced in 2019 to rapidly help confirm if a tsunami has been generated before it reaches our shores, buying us time. The more time we have, the more effectively we can react, which is particularly important for those tsunamis that come without obvious warning.

The deployment of the network follows many years of work. Commissioned by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT), with GNS Science (GNS) leading the science work, the network was built to deliver maximum benefit to Aotearoa and the Southwest Pacific. The strategic placement of the NZ DART network is designed to detect regionally-triggered tsunamis within 30 minutes of their generation anywhere within the South Vanuatu to Hikurangi subduction zones.

The true value of the DART systems lies in the ability to provide rapid confirmation that a tsunami is on its way and then improve our forecasts of its impact. Local tsunamis, those that are generated closer to home shores, limit the gift of time we have to act – amplifying the importance of nationally recognised and respected ‘Long or Strong, Get Gone’ messaging.

The DART network has already proven its worth on several occasions. In May this year, a small tsunami on coasts around the south-west Pacific was generated following a M7.7 quake 300 km to the south-east of the Loyalty Islands (900 km south-west of Fiji). The DART network detected the tsunami 50 minutes ahead of the first waves to reach New Zealand’s shores. In this time the science team was able to forecast the tsunami’s likely maximum height off the coast and impact and monitor the strong currents and surges that hit our coast until the waves abated four hours later. The DART measurements also showed us that the earthquake generated a bigger tsunami than would be expected for an M7.7 earthquake; it generated a tsunami about the size expected from an M7.8.

In January 2022, the DART network made a vital contribution to national security as tsunami experts raced against time to assess the threat we faced from the tsunami triggered by the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) eruption in Tonga. Without the DART network, New Zealanders would not have known a tsunami was imminent until it was picked up by the coastal gauges on our shores – too late for many to get to safety. Since then, analysis of our NZ DART data has been formally implemented in international tsunami warning procedures to respond to future tsunami-generating events like the HTHH eruption, making our partners in the southwest Pacific safer as well.

As well as contributing to the tsunami response caused by the Tongan eruption, the value of the network was also demonstrated in the response to the February 2021 Mw7.7 tsunamigenic earthquake triggered in the south of the Vanuatu Subduction Zone and in the March 2021 tsunami trifecta, where three tsunamis occurred within six hours.

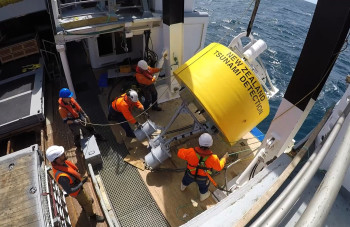

The DART systems are also useful in surprising ways. The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd (NIWA) undertakes voyages to service, maintain and refurbish the systems, visiting each within 24 months at sea. Part of that process is clearing off the aquatic organisms that have made a home under the DARTs, a process known as biofouling, which can obstruct the acoustic signals.

NIWA saw the opportunity to learn more about what species occur on each DART and how quickly they are moving around and settling on the buoys. This work is important as there are considerable gaps in our biodiversity knowledge in these areas. As climatic and environmental conditions change, species ranges in our oceans will change and these organisms will make their way to other places. If we can better understand these processes, it may help us protect our unique biota landscape from invasive aquatic species.

So, what is a DART network and how does it work?

The New Zealand DART network is an array of 12 separate systems that work to detect and communicate potential tsunami activity deep in the Pacific Ocean.

A DART system consists of two main pieces of equipment, a bottom pressure recorder (BPR) anchored to the sea floor, and a surface buoy, which works much the same as a floating radio. The BPR relays water pressure information by sending sound waves up through the water column to the buoy on the surface. The buoy then converts the data into wave heights and transmits the information via satellite to monitoring centres, including the New Zealand National Geohazard Monitoring Centre (NGMC) based at GNS Science in Avalon, Lower Hutt.

From deep on the ocean floor, many miles out to sea, the DART systems routinely capture data every 15 minutes . The information is transmitted to the monitoring centre at regular intervals. In the absence of unusual pressure changes, the data is parcelled up and comes through as a package every six hours. However, when a pressure change of significance is detected by the BPR, the DART system triggers and it will start to transmit at 15-second intervals for several hours, or until the water pressure returns to normal.

To see how the ocean wave activity is progressing, the NGMC team can manually trigger other DART systems situated nearby the one that has activated. By tracking pressure changes recorded by the instruments over time, the team can tell if a tsunami has been generated and promptly raise the flag, initiating an emergency response.

These alerts are also sent to the Rapid Characterisation of Earthquakes and Tsunamis (RCET) automated analysis system, where advanced methods are applied to rapidly investigate whether a tsunami is a threat to coastal communities and if so, when and how big the waves might be if they arrive at the shoreline, as well as how long before they abate and people can return safely to their homes.

Operating in one of the harshest environments in the world, the DART systems are positioned to ensure that any tsunami generated will be detected by more than one DART station. As well as providing for best coverage, careful placement of the systems allows consistent monitoring in the event of any damage or malfunction of any of the instruments. And in the deepest depths of the Pacific Ocean, damage is a situational hazard!

Scientists are still learning how to best support the DARTs. Each system is subject to a two-year replacement cycle, and each voyage to manage the equipment is a new opportunity to learn . A maintenance voyage is set to depart later this year and we will be sure to keep you up to date with the wonders of tsunami monitoring and the DARTs of the deep.

- Learn more about the DART programme by watching our video here

- And explore the NZ DART network data here

In the meantime, make sure you and your whānau stay tsunami-ready:

- Be prepared and know what to do and where to go should a tsunami warning be issued.

- Learn where the tsunami evacuation zones are for your area and make sure you know where to go to be safe, whether you are at home, at work or out and about. Plan and practise your evacuation route.

- Make sure you know the different ways to stay informed during an emergency. Learn which radio stations to listen to, which websites and social media to follow, and check if you can receive Emergency Mobile Alerts on your mobile phone.

- If you’re in a coastal area, and you feel a long or strong earthquake or abnormal movement of the coastal waters, don’t wait for an official warning. Move immediately to the nearest high ground, out of all tsunami evacuation zones, or go as far inland as possible.