Ngāuruhoe: the fiery history of Aotearoa's once-most active volcano

Most who have travelled through the winding Desert Road in the central North Island, will be familiar with the striking steep-sided cone of Ngāuruhoe volcano. Did you know that until 1975, Ngāuruhoe was the most active volcano in Aotearoa New Zealand, erupting every few years on average. Today we explore the history of this volcanic icon.

Mt. Tongariro is a large complex of volcanic cones and craters formed by eruptions from at least 12 vents over more than 275,000 years, known today as the Tongariro volcano complex. The cone of Ngāuruhoe is about 9000 years old, making it the youngest and highest (2291m high) portion of the Tongariro Volcano complex. It is considered to have a different source of magma to other recently active vents on Tongariro.

The introduction of maps in the 1800’s created confusion about the names of features in this area. The volcanic cone that is normally called Ngāuruhoe today, was known to the local Iwi as Tongariro and its summit crater as Ngāuruhoe (Aruhoe). However, after maps were published this changed due to mislabelling of some features.

Monitoring the volcano

Through the GeoNet programme, GNS monitors Ngāuruhoe as part of our wider monitoring in the Tongariro National Park (TNP). This increases our understanding of its activity and enhances the safety of visitors and people working around Tongariro National Park.

GNS Science supports volcano monitoring with web cameras, seismographs, acoustic sensors, GNSS/GPS and geochemical sampling of the hydrothermal system. Recently we added two additional specialised monitoring stations on Ngāuruhoe. The first measures temperatures of the fumarole on the eastern outer rim.

The second, a Multigas system automatically measures the concentration of Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂), and Hydrogen Sulphide (H₂S) gases. These gases are emitted through gas venting fumaroles on many active volcanoes and provide critical information for our volcano monitoring team.

View: Ngāuruhoe volcano camera

Read: Multigas system installed on Ngāuruhoe

Eruption history

Eruptions from Ngāuruhoe were well known to the local Iwi, with the first written accounts in 1839. Eruptive activity has ranged from phreatic events (steam-driven explosions that occur when water beneath the ground or on the surface is heated by magma, lava, hot rocks, or new volcanic deposits), through to phreatomagmatic events (eruptions that involves both magma and water, which typically interact explosively). There has also been fire fountaining and lava flows flowing down the side of the cone. Since 1839, numerous eruptions have occurred, with larger eruptive episodes in 1870, 1948-49, 1954-55, and 1974-75.

1870

An eruption in 1870 produced large steam explosions, scoria deposits, and the first documented lava flows on Ngāuruhoe.

1948-49

This eruptive episode started April 1948, with ash flows and ash columns reaching over 3000m. A lava flow resulted from the breaching of a lava lake over the rim of the crater in February 1949 and columns of ash generated by explosions reached heights of 6000m above the summit.

1954-55

The eruption from May 1954 to July 1955 is remarkable for the volume of lava produced. The eruptions started in earnest in June 1954 with lava fountaining, and two lava flows. Further lava fountaining and the largest lava flows occurred at the months end, with more fire fountaining, ash emissions and lava flows following in July, August, and September 1954.

Activity in 1955 was dominated by explosive ash eruptions creating may light ashfalls across the North Island and lava fountaining through to July.

Watch: Video of a lava flow during the 1954 eruption, via Te Ara website.

1974-75

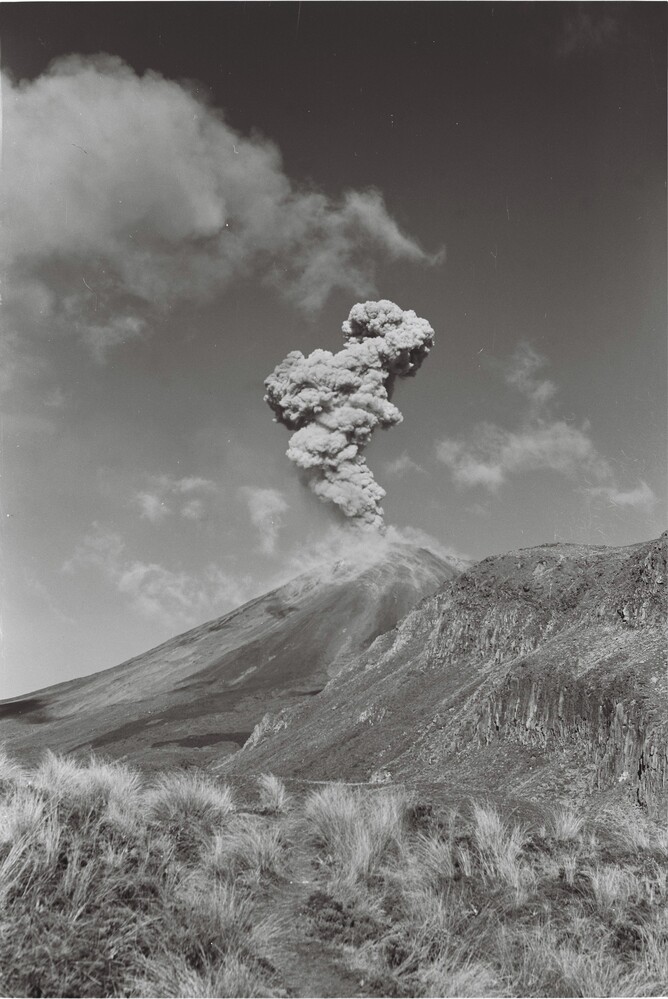

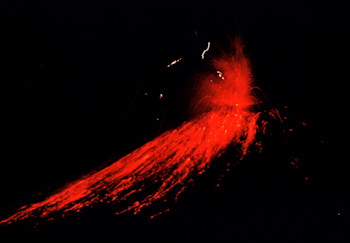

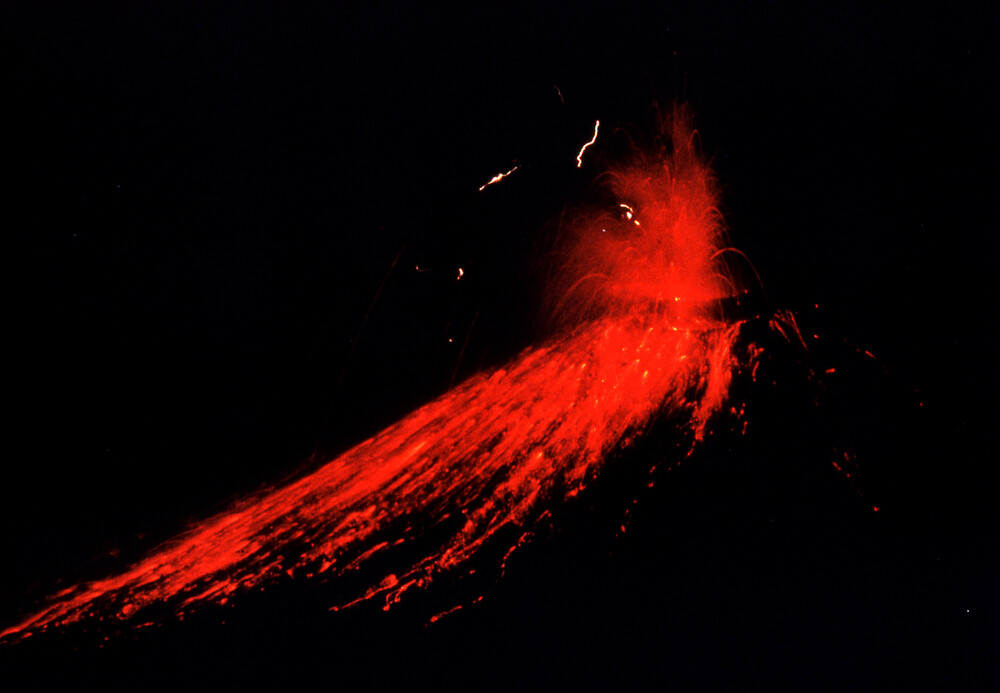

The 1974-75 eruptive episode produced many spectacular eruption plumes and pyroclastic surges (Ground-hugging clouds of ash, rock, and volcanic gas that move at rapid speeds and are extremely hot) travelling down the flanks of Ngāuruhoe.

Activity started in January 1974, with black ash clouds and tiny amounts of glowing material ejected from the volcano. After the initial explosion, ongoing activity followed, with violent explosions ejecting lava bombs that rolled down to the foot of the cone, and vigorous ash emission. This activity, although less explosive, continued through January.

On the 26 January the largest eruption since 1955 produced a dense ash column rising to 3800m that eventually underwent partial collapse to produce pyroclastic flows. Similar activity occurred again in late March 1974. Lightning was also seen at night in the ash clouds.

Activity levels increased again in February 1975, reaching a climax on February 19, with the largest explosions of the 1974-75 eruption episode. Intermittent eruptions generated pyroclastic flows down the flanks of the cone and ash columns that rose to 8300m that deposited fine ash as far as Rotorua, Hamilton, and Tauranga.

Recent volcanic unrest

More recently the volcano has shown signs of unrest in 2006-2008 and 2015 with increased seismic activity. In March 2015 this caused our volcano monitoring group to raise the Volcanic Activity Level (VAL) from 0 to 1. It was then lowered back to VAL 0 in April 2015, where it remains today.

Although Ngāuruhoe volcano is no longer our most active volcano, we continue to keep a close eye on It, along with all of Aotearoa New Zealand's volcanoes.

Planning on visiting the Tongariro National Park?

Find out more about Tongariro and other New Zealand volcanoes here.

For information on access to the Tongariro National Park area, please visit the Department of Conservation’s website on volcanic risk in Tongariro National Park and follow their Facebook page for further updates.

You can read all of our Volcanic Activity Bulletins here.

Although we can’t prevent natural hazards, we can prepare for them – and we should.

The National Emergency Management Agency's (NEMA) Get Ready website has information on what to do before, during and after volcanic activity.

During volcanic activity, follow official advice provided by your local Civil Defence Emergency Management Group, the Department of Conservation (for visitors to the Tongariro and Taranaki National Parks), local authorities and emergency services.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for natural hazards. Toka Tū Ake EQC’s website has key steps to get you started.

Media contact: 021 574 541 or media@gns.cri.nz