Unravelling the Mysteries of UTC

Welcome, haere mai to another GeoNet Data Blog. Today’s blog is about a technical choice we’ve made in relation to GeoNet data and data products, and explaining that to our everyday data users.

If you have ever had reason to dig into any GeoNet data, you may have noticed we normally describe when something happened using Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), let’s dive in for a closer look.

Time zones

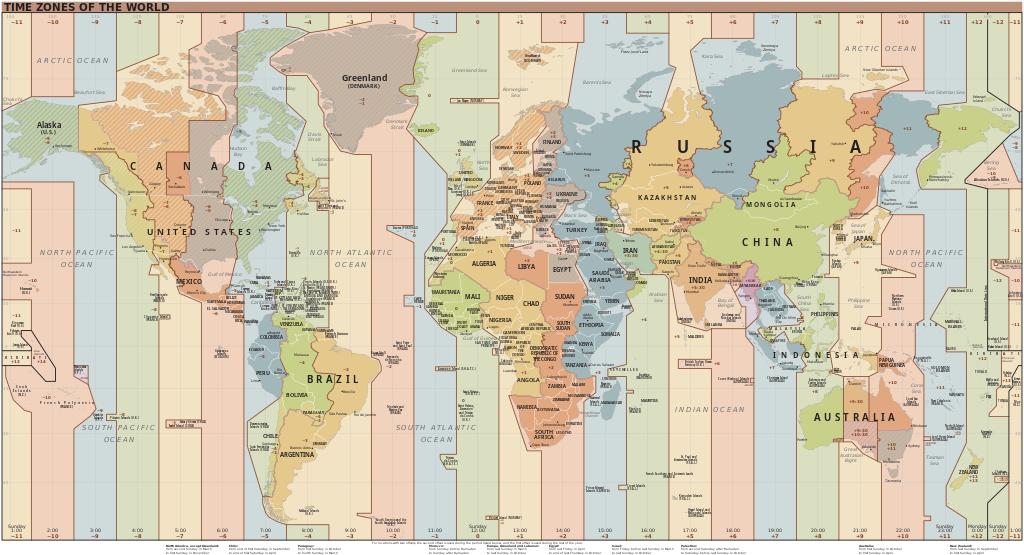

Before we jump into UTC, let’s take a short look at time zones as they are intimately linked. Most of us understand the concept of time zones. When its 3 PM in Aotearoa New Zealand, its 1 PM in Sydney and in Los Angeles its 8 PM yesterday. When we fly to places overseas, we have to change our watches to match the time in the place we are arriving in – on arrival in Sydney we put our watches back 2 hours.

The Earth rotates on its axis once a day, and time zones ensure that the sun rises when our watch says it’s about 7 AM and not 3 PM or some other time that doesn’t make sense. The Earth has 24 main time zones and quite a few “odd balls”.

All time zones are referenced to a global time standard called Coordinated Universal Time, abbreviated as UTC. Time zones are listed as being ahead of UTC such as UTC+12:00, which is New Zealand Standard Time (NZST), or behind UTC such as UTC-08:00 which is the time zone of Los Angeles and is called Pacific Time (PT). All of our computers receive UTC as part of being connected to the internet, and then display the time zone chosen by the computer user.

Why does GeoNet use UTC?

All GeoNet data use UTC to indicate when something happened. Unlike “local time”, in our case New Zealand Standard Time (NZST) or New Zealand Daylight Time (NZDT), UTC is the same everywhere. Some of you may be familiar with Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). UTC and GMT are effectively the same, with UTC superseding GMT as the preferred name about 50 years ago. If you are interested, Wikipedia has a comprehensive explanation of UTC.

Given GeoNet collects (pretty much) all of its data in New Zealand, why do we use a global time standard based on the time half a world away?

The answer lies in the fact that earthquakes and tsunami and many other natural phenomena can affect the whole world. For example, a large earthquake occurs in east Asia and triggers a tsunami. If local authorities near the earthquake notify everyone around the Pacific Ocean that the quake occurred at 5 AM local time, those receiving the information may not know what time zone that was, so may not be able to confidently work out when the potential for a tsunami threat to New Zealand may start. To avoid confusion about when major events occur, it’s far safer for everyone to work in UTC.

These days, we all use GPS for navigation (in our cars and even some of us on our bicycles), and GeoNet, and most similar agencies, use the same satellite signals for setting accurate and consistent time in the instruments we use to collect data. Satellites circle the globe and must have a uniform and consistent time system, which is UTC. This means that internally all our instruments “think” in UTC, and from there it’s a logical step that all our data use UTC as a time system.

The use of UTC for our data extends to our metadata, data processing systems and services. Delta, our sensor network database that powers all our data delivery applications, is also in UTC.

Internally, there are still some users and systems that “think” and work in local time. Much of the manually collected volcano data, especially that involving samples that are later analysed in a laboratory, are labeled in local time, for practical reasons that they are mostly used and interpreted locally. But, when we get the numeric data from these analyses and load them into the Tilde data delivery application, we convert to UTC for consistency with all other GeoNet data and to enable them to easily be shared everywhere.

What does UTC look like?

So, what does UTC look like and how do we indicate that it is used in GeoNet data? There are a couple of common ways of indicating UTC when giving a date and time. The clearest is to simply follow the date-time by the letters “UTC”. The other is to follow the date-time by the letter “Z”, which stands for “Zulu time”. In GeoNet, we use the Z method to indicate UTC, for example, 2024-04-25T19:25:53Z. The order of the date is year, then month, then day, each separated by a dash “-”, and the hours, minutes, and seconds are separated by a colon “:”. The date is separated from the time by the letter “T”, and the “Z” comes at the end. This format is an international standard called ISO8601 and GeoNet uses it for all our UTC dates and times.

Making it less confusing

In some cases, we show the local time of some data while working in UTC in the background. We do this because UTC and how it relates to the time shown on our watch (or more likely smartphone) is confusing to many. Recent Quakes, the most widely viewed page on our web site, does this. But the technical tab of each quake shows the corresponding UTC time. If you look at the Quake Search page, the date-time in the search is expecting UTC, and any files you might create only show date-time in UTC. But if you look at the map view of your quake search and click on one of the quakes, the origin time is shown in NZST or NZDT.

Another situation where local time is to the fore is in our Volcanic Activity Bulletins (VAB). The issue time of these is given in local time, and within the body of a VAB any references to dates use local time. Closely related are Volcanic Alert Levels (VAL) that are shown in each VAB. When we provide the VAL as a data set, we try to cater for “both sides of the fence” with date-time in both UTC and local time. This works well for both technical and general users.

In GNS Science where staff gather during an event response, there are two clocks, one showing local time and one UTC. In the stress and excitement of responding to an event even experts can make mistakes, so we’ve taken steps to try to avoid that.

Converting to and from UTC

NZST to UTC - Subtract 12 hours. 8 AM local time is 20:00 UTC the previous day, and 3 PM local time is 03:00 UTC the same day.

UTC to NZST - Add 12 hours. 08:00 UTC is 8 PM the same day, and 22:00 UTC is 10 AM the following day.

NZDT to UTC - Subtract 13 hours. 8 AM local time is 19:00 UTC the previous day, and 3 PM local time is 02:00 UTC the same day.

UTC to NZDT - Add 13 hours. 08:00 UTC is 9 PM the same day, and 22:00 UTC is 11 AM the following day.

If you don’t remember, NZDT is used from the last Sunday in September to the first Sunday in April.

That’s it for now

If you’ve often wondered why the date and time on GeoNet data seemed a bit unusual, now you know, it’s all about UTC. Remember, all GeoNet data are stored in UTC, and all data delivery applications use UTC in the background. But some of our data products provide local time first (in the front) with UTC available behind for users wanting to work with multiple data sets. Converting to and from UTC is just a matter of adding or subtracting 12 hours, or 13 hours when we are using Daylight Saving.

You can find our earlier blog posts through the News section on our web page just select the Data Blog filter before hitting the Search button. We welcome your feedback on our data blogs and if there are any GeoNet data topics you’d like us to talk about please let us know!

Ngā mihi nui.

Contact: info@geonet.org.nz