Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano – information about the eruption

Updated: Fri Jan 21 2022 11:00 AM

As of today, information we have access to indicates that the volcano is not currently erupting, and we have not detected further tsunami activity. Volcanologists are still building a picture of what happened during this globally significant eruption.

GNS Science’s 24/7 National Geohazards Monitoring Centre continues to monitor DART buoy and coastal tsunami gauge data that could tell us if another eruption has occurred that caused a tsunami. Satellite imagery may also help us to determine if an eruption occurred. We wrote a story earlier this week on the tsunami generated by the eruption and how the DART buoys worked.

We are working alongside other government agencies to provide support where we can.

About the eruption

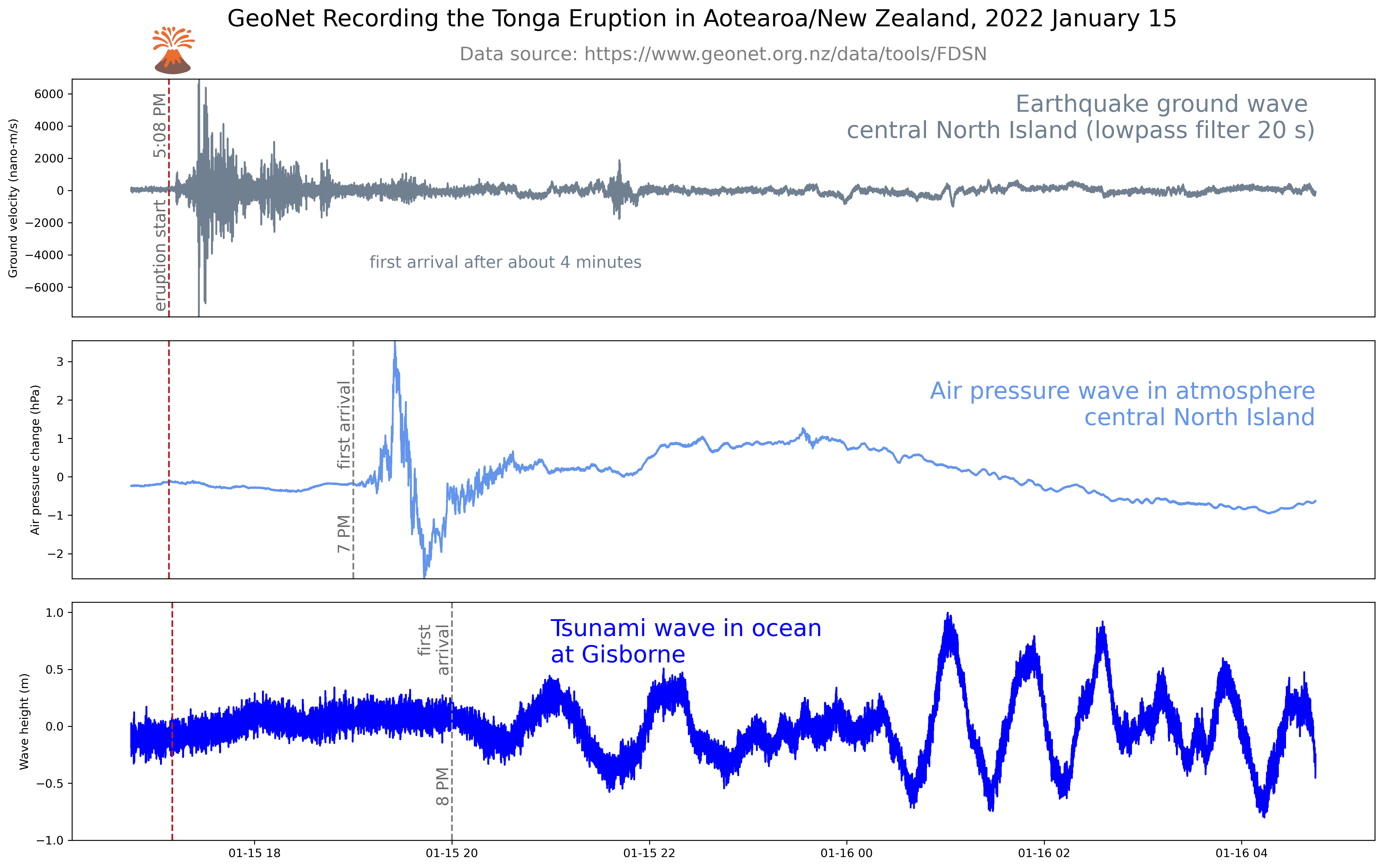

A very large, explosive eruption occurred at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga on 15 January 2022. The eruption was very energetic, generating a tall eruption cloud, explosions, shockwaves, audible booming and it created tsunami waves that travelled around the Pacific.

The huge eruption was the largest in the current eruptive episode at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai that spans back to 2009. Back then, all you could see of the volcano was two small, elongated islands poking about 100 metres out of the ocean. Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano is located 65 kilometres north of Tonga’s capital Nuku‘alofa

During 2014 and 2015 eruptions, a cone built at the volcano, bridging the gap between these two smaller islands to create one larger island.

An earlier eruption on Friday 14 January destroyed this central cone, flooding the vent with seawater. This added to the instability of the volcano, and the addition of large amounts of water may have contributed to the Saturday 15 January eruption being more explosive. The eruption exploded through the ocean, triggering a tsunami, with waves that headed for coastlines right around the Pacific Ocean. All that remains now of the volcano above water are two much smaller islands again.

Volcanologists’ initial assessments indicate that about 0.5 to 1 cubic km of volcanic material was ejected. The eruption and gas plumes rose approximately 30 km into the sky in a Plinian eruption – the term volcanologists give to eruptions that form tall ash columns into the stratosphere. We're working hard to decipher the data that we are gathering on the eruption to build a more complete picture of what happened.

The eruption was much more violent than scientists had expected, given the volcano’s run of smaller eruptions in recent decades. The atmospheric shockwave travelled around the globe several times and was picked up on air pressure sensors as far away as Iceland - it continues to circle the globe. Audible booming could be heard from New Zealand to the south and Alaska to the north. This was due to the low-frequency bass-like booms produced during the eruption that can travel thousands of kilometres away from the source. This eruption now holds the world record for being ‘heard’ so far from the volcano.

The eruption was rare in that it caused tsunami waves large enough to impact thousands of kilometres away from the volcano. There are several mechanisms scientists believe could have contributed to generating tsunami waves: the huge explosion through the ocean, the shockwave that pushed out as it travelled, the effect of the collapsing eruption column onto the ocean, and a possible caldera collapse of the volcano itself underwater. We haven’t seen a volcanic-source tsunami like this since Krakatau, Indonesia in 1883.

While the submarine eruption and tsunami is a rare combination in our lifetime, it’s not unprecedented. Scientists have been highlighting the possibility of submarine eruptions as tsunami sources for decades.

Our scientists expect that the volcano will remain active for weeks to months, and small eruptions will once again build up a cone above sea level.

The international volcanology community is continuing to keep tabs on activity at the volcano by looking at satellite images.

Volcanoes can erupt without warning. We monitor all New Zealand’s active volcanoes for signs of activity and provide updates of activity via Volcanic Alert Bulletins if there are any significant changes to report. To read more about being prepared for volcanic activity visit the National Emergency Management Agency’s (NEMA’s) website, getready.govt.nz.

Attributable to: Steve Sherburn – GNS Science Duty Volcanologist

Media contact: 021 574 541 or media@gns.cri.nz