Shaking ground: Exploring earthquake faults

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, we have faults everywhere, but what exactly are they? And why do they mean we have earthquakes?

New Zealand has a unique geographical and geological place in the Pacific, sitting on the boundary between the Australian Plate and the Pacific Plate. These two plates are continuously moving against or past each other, often they're stuck, and stress is just building up. In some cases, this stress can be relieved over time by a process called Slow Slip Earthquakes which are unnoticed by people. Most of the time though, this stress causes faults to move suddenly and create earthquakes that we feel.

So, what is a fault?

A fault is a fracture or a plane of weakness in the earth’s crust. It can be as short as a few metres or as long as a thousand kilometres. When an earthquake occurs, the land on one side of the fault slips with respect to the other.

Watch our video below to see how they cause earthquakes:

Do they all move the same?

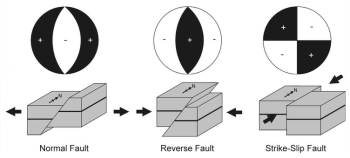

Land can move in several different ways during an earthquake. The type of earthquake can change how energy radiates from the earthquake source, and in turn, how it is felt at the surface. An example of how the slip-type impacts earthquakes is when we have two earthquakes that look similar in size and depth on our website, however, one may have a larger shaking intensity (e.g. light shaking vs moderate shaking). This is because the two earthquakes have different focal mechanisms. This gives the earthquakes quite different shaking on the surface, as how the energy spreads will depend on the type of focal mechanism. You can view different fault movements in action via our short video on YouTube.

Scientists can tell the slip type of larger earthquakes, by producing what we call focal mechanisms. These graphics are a way of showing the fault, and direction of slip from an earthquake, using circles and curves. They’re often nicknamed ‘beach balls’!

How do we know where faults are?

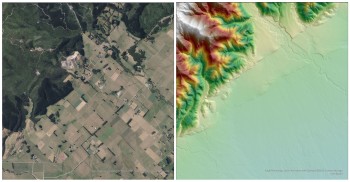

With larger faults we can often see them clearly in our landscape. Large faults with the potential to generate big earthquakes – like the Alpine Fault – will form a significant line in New Zealand's landscape and are therefore much easier to find. Some faults, though, are harder to detect as they can be shorter, have earthquakes less frequently, or are in areas where evidence of the fault line is quickly eroded away. For example, where faults cross river valleys and floodplains they can be covered up quickly by the accumulation of river sediment.

For these faults that are harder to see, technology makes the job easier. We use LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data to help map and identify faults – large and small. LiDAR is a remote sensing method that uses light energy from a laser, directed at the ground from a drone or plane. It measures distances to the Earth surface and enables us to build high resolution (1 m) 3D models of the ground surface and can help see the ‘bare earth’ that is obscured by dense vegetation, as shown below.

Our Data

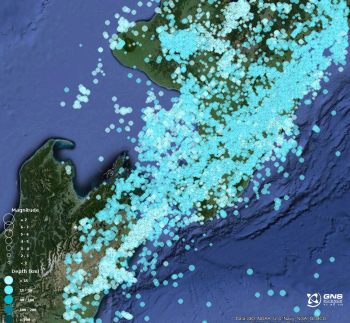

Our active faults database contains over 500 mapped faults in New Zealand that are capable of magnitude 6+ earthquakes. Although the amount of known active faults has increased significantly in the last few decades, there are still many unknown faults capable of producing large earthquakes.

We also know where earthquakes have occurred in the past, and with a searchable database of over 480,000 earthquakes we know where a lot of faults in New Zealand are. The trouble is that all these earthquakes don't nicely line up and show all the individual sub-surface faults. The image below showing just two years of shallow earthquakes (less than 40km deep) in the middle of the country illustrates this. Also, as large quakes are infrequent. Without the data from all types of earthquakes, large and small it's impossible to know whether the small quakes are occurring on a small fault, or they're small quakes occurring on a small portion of a larger fault.

This is one of the reasons why GeoNet embraces its role as a steward of our datasets, and makes them open to all: to help the science of the future grow our knowledge and understanding of our natural hazards.

Want to learn more?

Watch our video - Why do we get Earthquakes in New Zealand.

And keep an eye out for our next update, where we will take a look at one of our biggest faults in New Zealand, the Hikurangi subduction zone.

Earthquakes can occur anywhere in New Zealand at any time. In the event of a large earthquake: Drop, Cover and Hold.

Remember Long or Strong, Get Gone : If you are near the coast, or a lake, and feel a strong earthquake that makes it hard to stand up OR a weak rolling earthquake that lasts a minute or more move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can, out of tsunami evacuation zones.

Know what to do?

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) has a great website with information on what to do before, during and after an earthquake.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for natural hazards. Toka Tū Ake EQC’s website has key steps to get you started.

Media Contact: 021 574 541 or media@gns.cri.nz