M 7.8 Kaikōura Mon, Nov 14 2016

At 12.02 a.m., on Monday 14 November 2016 NZDT, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck 15 km north-east of Culverden, North Canterbury, starting near the town of Waiau.

- Date: 14 November 2016

- Source: Local

- Cause: Kaikōura earthquake

The tsunami was the biggest local-source tsunami in New Zealand since 1947 (and by local-source we mean a tsunami created close to our shore rather than a distant-source tsunami created on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, for example). It was unusual in that it was generated from an earthquake that started on land and crossed the coastline offshore – that’s pretty rare. It was also unusual because of the number of offshore faults that moved. This unique combination meant that the tsunami behaved a little differently from your more standard tsunami generated from only one fault.

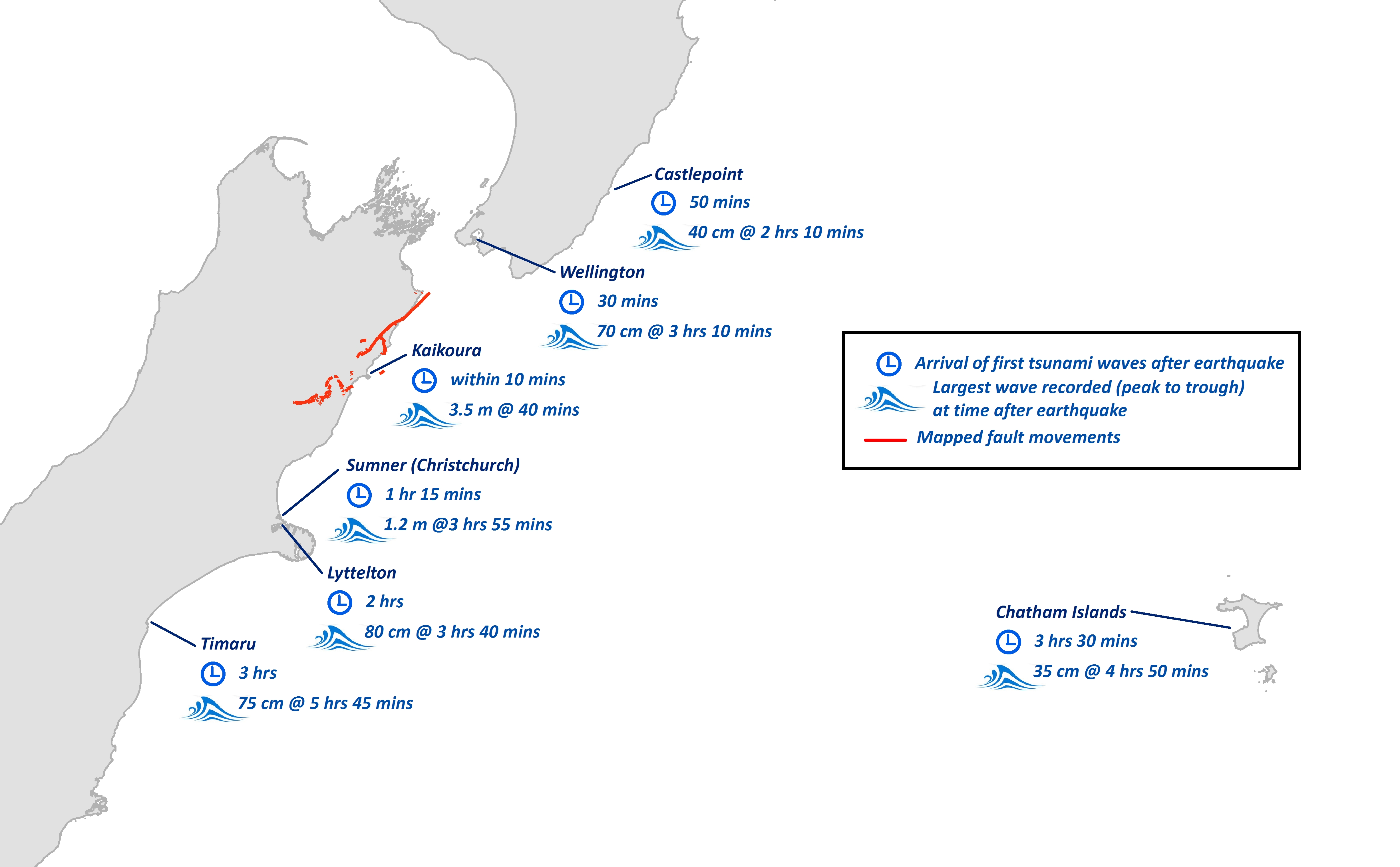

The map below shows where water level gauges recorded the tsunami. The wee clock is how long after the earthquake that the first tsunami waves arrived, and the wee wave is the maximum tsunami wave recorded and the time after the earthquake that it was recorded. The maximum wave in this case is measured from peak to trough (that is, the largest change in water level from the top of a wave to the bottom, rather than the largest height above normal sea level at the time).

As you can see the first waves reached the Kaikōura coast within 10 minutes of the earthquake – a good reminder of why you need to move away from the coast quickly if you feel a long or strong earthquake (like most Kaikōura coastal residents did on the night – go you guys!). Ten minutes may not be long enough for our seismologists to confirm a tsunami has been generated, and for Civil Defence to issue an official warning to everyone – natural warnings are the best warnings.

You may have read that the tsunami was 7 metres high near Kaikōura. This sounds huge, but it’s not quite the 7 metre wall of water at the coast that it sounds like. This figure referred to the 6.9 metre ‘run up’ measured in Goose Bay, just south of Kaikōura. The tsunami wave height in the sea was probably around 3-4 metres above the normal sea level at the time when it reached Goose Bay, but the beach there is very steep and the wave pushed up against it, leaving debris up to 6.9 metres above sea level. The tsunami also pushed at least 150 metres up the Ote Makura Stream in Goose Bay and over 200 metres up Te Moto Moto stream in Oaro.

The tsunami certainly came out of left field for the seaweed and other unfortunate aquatic life, including koura (crayfish) and paua and various fish, who were also left high and dry 3-4 metres above sea level at other locations along the Kaikōura coast and at Needles Point in Marlborough.

On the whole, the damage along the Kaikōura coast from the tsunami was less than we might have expected because the tsunami arrived at mid to low tide, much of the Kaikōura coastline was uplifted during the earthquake, and the beaches along the coastline here are steep. Otherwise the damage could have been much worse.

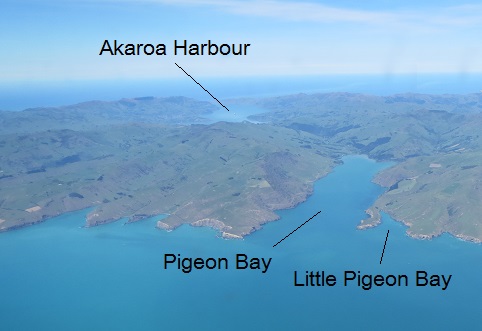

The other unusual aspect about the tsunami was that the worst damage happened 150km away from where the tsunami started. The tsunami waves would have been almost unnoticeable as they silently travelled south through the open waters off the North Canterbury coast. But once they got to Banks Peninsula (whose narrow bays and harbours have been described in the past, by someone who shall remain nameless, as ‘a collection of funnels waiting to receive tsunamis’) 1.5 hours after the earthquake, north-facing Little Pigeon Bay sat at just the right angle for the waves to flow straight into it, and it was just the right shape for the waves to start bouncing around inside the bay. This particular mix of circumstances created tsunami surges at the head of the bay that were bigger and more forceful than those seen in other northern Banks Peninsula bays.

A historic cottage at the head of the bay was flooded by the tsunami and lifted partially off its foundations. Two verandas were torn off – one was later found floating in the bay and the other was never recovered. But it wasn’t just the water that did the damage – the cottage was battered by debris that the tsunami picked up on its way through, including some large sawn tree trunks that had been sitting on the beach. One of these logs battered down the front door and stove-in the wall beside it. The water even moved a power pole that had been lying on the ground 5 metres inland. The tsunami run-up was only 3.2 m above the sea level, but the inundation reached 140 m inland. Interestingly the cottage was also flooded, to a lesser degree, during the 1960 Chile tsunami.

The damage to the cottage is a good reminder that it’s not just the height of a tsunami wave but the sheer power behind an enormous mass of moving water, and the assorted flotsam and jetsam that it’s carrying, that can make tsunamis so dangerous.

The differing impacts from the Kaikōura tsunami along the eastern South Island and southern North Island coasts show us again what tricky little beasts tsunamis are. Scientists work really hard to understand tsunami behaviour so that they can provide better information to people both before and during a tsunami. Because this event was so complex, scientists are still working on a model to explain how the fault movements during the earthquake caused the flooding and impacts seen on land.

A very important, but not unusual, aspect of the tsunami was that in most places (apart from very close to where the tsunami started) the highest tsunami waves arrived a couple of hours after the first wave. While an official warning can’t replace the natural warning of the earthquake itself (that’s right – long OR strong earthquake, get gone!), our seismologists will still work closely with the National Emergency Management Agency (who issue tsunami warnings) to advise people of a possible local source tsunami, even if the first waves may have already arrived. This is because (a) it confirms to those coastal residents that did evacuate when they felt the long or strong earthquake that it was a good idea, and that they should stay away for the time being and (b) the largest tsunami waves may still be on their way, so for people who haven’t already evacuated, it’s still a good idea.

One last thing: we often get asked “how far up or inland am I meant to go”? Which is a really good question. You can find your region’s tsunami evacuation zones on your local authority’s CDEM website – you can find a link to these on the National Emergency Management Agency’s website. You only need to go inland far enough that you are out of the tsunami evacuation zones. It is best to go on foot or bike if you can, to leave the roads free for those who really need to drive (if you are in a car you might like to drive a wee bit further to make room for those coming behind you). Have a look at your tsunami evacuation zones – it might not be as far as you think. Or you may not even be in a tsunami evacuation zone at all, which means after you feel that long or strong earthquake you can stay put and open your doors for your friends and family who may be turning up from nearer the coast.

Science contacts:

William Power, GNS Science, w.power@gns.cri.nz, Emily Lane, NIWA, emily.lane@niwa.co.nz